Discussed on lobste.rs and Hacker News.

Two people. Eighteen accounts spanning checking, savings, credit cards, investments. Three currencies. Twenty minutes of work every week.

One net worth number I actually trust.

The payoff: A single, trustworthy net worth number growing over time.

No app did exactly what I needed, so I built my own personal finance system using plain-text accounting principles and a powerful Python library called Beancount. This post shows you how I handle imports, investments, multi-currency, and a two-person view.

How I got here

It all started during the 2021 tax season. I had blocked out an entire weekend and was juggling statements, trying to compute capital gains, stressing about getting the numbers mixed up. “This is chaos”, I thought. “There must be a way to simplify this with automation”. Being a software engineer, I did what felt natural and hacked together a bunch of scripts on top of a database.

Though it worked and I kept using it day-to-day, by the next tax season the cracks became obvious. The code was hard to debug, random transactions went missing, and worst of all, the balances the scripts computed didn’t match the balances on my statements. I tried to fix it but the more I tried, the more I felt lost about what the system was really doing. Eventually I just gave up.

Why did I fail so spectacularly? My entire approach was flawed from the start! I’d ignored centuries of accounting wisdom and repeated fundamental mistakes humanity solved long ago. So I learned from my mistakes and did the research. And over time I incrementally discovered double-entry bookkeeping, plain-text accounting and Beancount.

Fast forward to today, and I have a flexible, powerful, and private system, fully customized to how my brain works. Most transactions import automatically from PDF statements (counterintuitively, it’s often more reliable than CSV!). Tax time is a simple matter of checking always-fresh reports and copying numbers over. The weekly ritual is simple: download statements, categorize transactions in a web UI, run a bunch of scripts to regenerate, commit (I walk through this in more detail later).

However, I want to be realistic: building a system like this takes time and effort.1 You will need to learn some basic accounting concepts, be comfortable with Python, and consistently spend time every week keeping things up-to-date. If your finances are simple or you just want day-to-day budgeting, this is almost certainly overkill. Apps like YNAB or even the humble spreadsheet work great.

But if you want uncompromising control over how you look at your finances, read on.

Chapter 1: The Concepts

Double-entry bookkeeping

Suppose on a Saturday, I transfer money from my checking account to a savings account. The money leaves on the same day but doesn’t show up on the other side until Monday. So where was it for those two days?

In a “normal”2 personal finance system, the answer would be that it was just gone. That is, for those two days, there would be a drop in the total money in two accounts. But this is weird because in reality my “net worth” did not change, yet there’s no good way to represent this.

Or suppose I pay $90 for a dinner for me and two friends. They pay me back a week later. Again, in this case the money is “gone” for that week. And even worse, the full $90 would be categorized as a “restaurant expense” while each $30 my friends paid would be “income”. But this is wrong. My expense is just $30 and the money they give me should be matched against the $60 they owe me.

Both of these are fundamental problems with how so-called “single-entry bookkeeping” works: each account’s transactions and balance are tracked individually but without the context of the “whole”. In the case of the transfer, because we’re looking at each account in isolation, we lose the fact that even though the money has left one account, it’s really still part of the “pool of money” that belongs to us. Similarly, when our friends pay us back, we’re not tracking the fact that our friends owe us money when the original transaction happened and their payment later neutralizes the debt.

Double-entry bookkeeping is the solution to both these problems. Businesses have been using it for hundreds of years3 to run their accounts, and it has powerful yet elegant ways to solve these problems and many others too.

Let’s consider again the transfer. In double-entry bookkeeping, we would represent the initial move of money as:

Bank-Checking -1000

Transfer-In-Flight +1000

And when it arrives:

Transfer-In-Flight -1000

Savings-Account +1000

In both cases, we see the “golden rules” of double-entry bookkeeping:

- Every transaction has at least two sides and the sum of all the sides is zero. -1000 + 1000 = 0. That is, transactions always “balance”.

- Every side of a transaction is an account, whether it exists in the real world or not.

It should be clear that “Bank-Checking” and “Savings-Account” are labels for your checking and savings accounts, respectively. But what is “Transfer-In-Flight”?

Well, it’s also an account! It’s not an account you’ll find on your bank’s website, but within the double-entry system, it’s just as real. Concretely, accounts in double-entry are just labels for a “bucket of money”. So there’s no “category to put this transaction under”, no “expense tracking”, no special “transfer tag”. Everything is an account.

In this specific case, Bank-Checking, Savings-Account, and Transfer-In-Flight are all a specific type of account: they are Asset accounts. Assets are stuff you own; these can be real accounts (bank account, savings, stocks, bonds) or conceptual accounts (money in transit between accounts).

Now let’s consider the dinner example. There are 4 sides to the transaction:

Credit-Card -90

Restaurant-Expense +30

Owes-Me:Alice +30

Owes-Me:Bob +30

Again, -90 + 30 + 30 + 30 = 0. It balances. All of Credit-Card, Restaurant-Expense, Owes-Me:Alice, and Owes-Me:Bob are just accounts.

Credit-Card is a different type of account though: it’s a Liability. Liabilities are the opposite of assets: instead of stuff you own, they’re stuff you owe to someone else. So for example, loans, credit cards, and mortgages are all liabilities.

Why negative 90? The rule is always: negative means money flowed from this account and positive means it flowed into this account. The credit card company fronted you $90, so that money flowed from your credit card to fund the purchase.

Restaurant-Expense is yet another type of account, an Expense account. Expense accounts are money “leaving your world”. So any time you spend some money and you no longer have access to it, that’s an expense.

Finally, Owes-Me:Alice and Owes-Me:Bob are also Assets. Alice and Bob have promised to pay you back, and that promise has value, $30 each. It’s not cash in your pocket, but it’s money you have a claim on. In double-entry, anything with economic value you control is an asset, whether it’s a bank balance or an IOU.

Later, when Alice pays you back:

Bank-Checking +30

Owes-Me:Alice -30

This is just money moving from the “virtual” Owes-Me:Alice to the “real” Bank-Checking account. Both of these are still assets; it’s just the type of asset that’s changing. So no money has “entered the system” at this point. You’re just settling the debt Alice owed you.

Let’s take one last example: a paycheck.

Bank-Checking +3000

Salary -3000

Bank-Checking is an Asset as we’ve learned. But Salary is a new account type, an Income account. Just like Assets and Liabilities are opposites, so are Income and Expenses. Where Expenses are money leaving your world, Income is money entering it.

Money flowed from Salary (source, negative) to Bank-Checking (destination, positive). The sign feels backwards: “I received money, so why is Income negative?” Because the sign shows direction of flow: income is where the money came from, and your bank is where it went to.

This is the one part of double-entry that takes repetition.4 Don’t try to make it intuitive; just trust the invariant: if your transaction sums to zero, you’ve got the signs right. After a dozen transactions, the pattern becomes automatic.

These four types of accounts cover 99% of what you’ll do:

- Assets: stuff you own (bank accounts, cash, investments, money owed to you)

- Liabilities: stuff you owe (credit cards, loans)

- Income: money entering your world (salary, interest, dividends)

- Expenses: money leaving your world (groceries, rent, restaurants)

There’s a fifth type, Equity, which is a catch-all “this money doesn’t fit elsewhere” bucket.5 Suppose you start tracking an account that already has $1000 in it; that money came from somewhere but you don’t have a record of that. It can’t be income because you already had it, and the other types don’t fit. That’s a good sign it belongs in equity. The good news is that you rarely interact with Equity directly. Generally, the software handles it for you, but there are some exceptions that we’ll cover in Chapter 2.

There’s so much more that could be said about double-entry bookkeeping. For further reading, I particularly like the double entry explainer in the Beancount docs. It goes through some more examples and expands into a bunch of related topics.

But we now have the foundation which ensures that every transaction balances, every dollar is accounted for, and nothing slips through the cracks. But we still need a way to actually record and store these transactions.

Plain text accounting

One of the things I learned from writing my own finance system is that auditability is king. You need the ability to eyeball a transaction, ask yourself “does this look right,” and fix it if it doesn’t. And nothing beats being able to see and edit any transaction you’ve ever made in a text editor.

That’s one of the main things that drew me to the philosophy of Plain Text Accounting. This is a set of principles on using plain text files as the “immutable source of truth” of your finances and then building scripts and tools on top of them to process, analyze, and visualize them.

There are many other advantages to this I’ve come to appreciate over the years:

Everything is version controlled. You can store these transaction files in a git repo, which has powerful effects. You can look at diffs to see what changed on any day. You can git blame any transaction to see when and why it was added. You can git tag important states of the repo (e.g. when taxes were filed, when a new job was started, when a big refactoring happened). You can git checkout any previous state to see e.g. “how did my repo look last year”.

It’s private so you never have to trust any third party with all your financial details. Everything can be stored in locations that you fully control.

There’s no lock-in. Because everything is just a plain text file, it’s trivially easy to change how you want things to be represented: you don’t have to deal with apps with broken or messy CSV exports making it difficult to take your data elsewhere.

It’s scriptable. If you want to refactor something, compute a new breakdown or even rewrite your system entirely, all you need is to write a script. Whether you write it yourself or prompt an LLM to do it for you, the text-based format makes automation trivial.

Plain text gives you the abstract idea of “storing transactions in text” but there’s still a bunch of questions. What’s the transaction syntax? How do you parse your files? How do you validate that everything balances, compute totals, and let you query the results? That’s where Beancount comes in.

Introducing Beancount!

Over the years, people have written many plain-text accounting tools which answer all the questions above. The main ones you’ll find which have gained a lot of popularity are Ledger, hledger, and Beancount. I’ve used each of them at some point in my plain text journey and all are solid choices. But I ended up on Beancount for a few reasons.

It’s a Python library, not just a command-line tool. I can write importers that parse my bank’s PDF statements, generate transactions programmatically, and build custom reports, all in a language I already know.

Strictness by default. Accounts must be declared before use, so typos get caught immediately. Transactions must balance and there are immediate error messages if they don’t. The tool catches mistakes early rather than letting them propagate.

Plugin and tool ecosystem. Beancount has a very rich set of libraries and tools which build on top of and integrate with it. Along with the core project, you get access to any and all of these projects you want to use. We’ll discuss this much more later.

Fava. The web UI which sits on top of the Beancount engine. It’s so good that people convert from other formats (using tools like ledger2beancount or gnucash2beancount) just to use it. Where Beancount gives you the reliable engine, Fava gives you the pretty yet powerful frontend:

- Reports: balance sheet, income statement, transaction journal

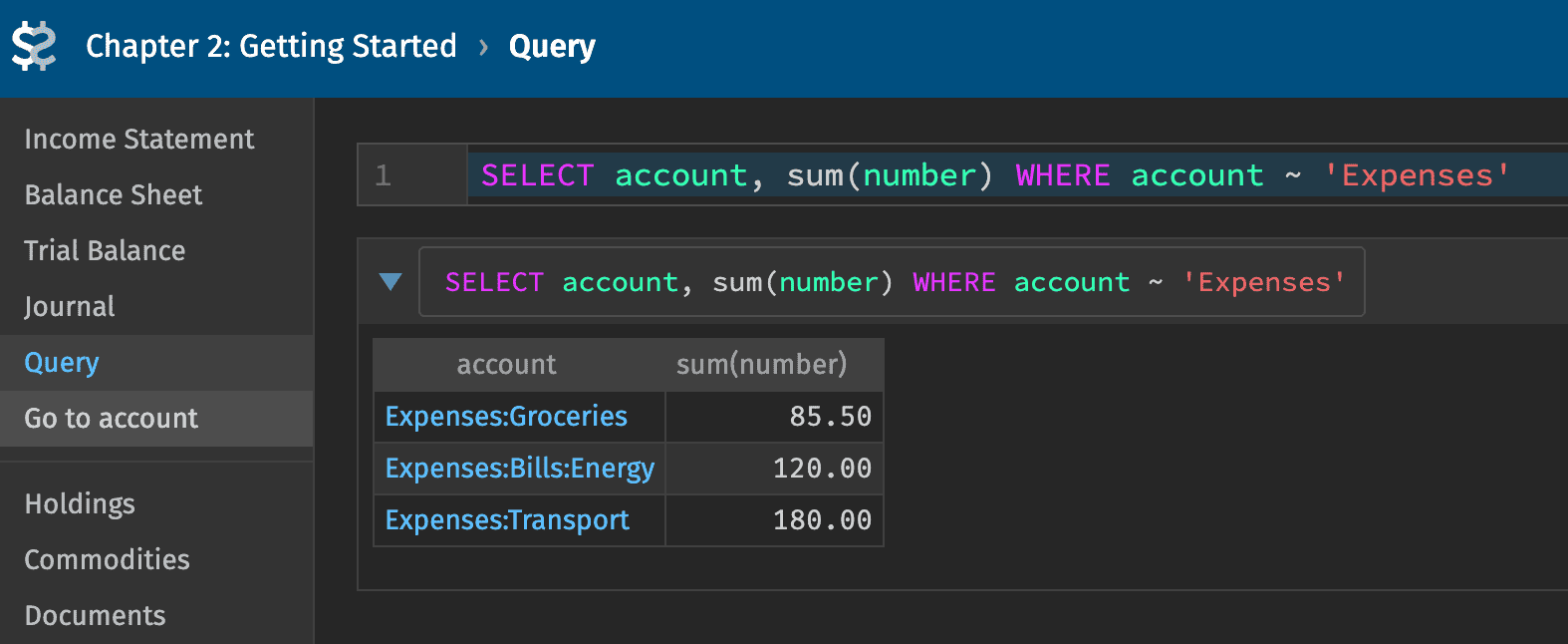

- Query editor: SQL-like queries, exportable to CSV

- Charts: spending breakdowns, net worth over time, holdings by currency

- Error highlighting: problems highlighted immediately

- Extensibility: plugins like fava-dashboards and fava-portfolio-returns

With this, we now understand enough of the basic concepts for us to get started trying out Beancount!

Chapter 2: Getting Started

The best way to learn plain-text accounting is to roll up your sleeves and try it out. So let’s pause the theory for a moment and get a real ledger running on your machine.

I’ve built a companion repository, LalitMaganti/beancount-blog-examples, which contains a cut-down version of the system I use day-to-day. The repo is organized into folders that match the chapters of this post (chapter-2/, chapter-3/, etc.), each building on the previous. It also includes a demo/ folder with 2+ years of synthetic history if you want to see the end result immediately.

To get started, clone the repository:

git clone https://github.com/LalitMaganti/beancount-blog-examples.git

cd beancount-blog-examples

# Run the demo to see the end result

./scripts/quickstart.sh demo

# Or start Chapter 2 to follow the guide

./scripts/quickstart.sh chapter-2

This will set up a Python environment, install dependencies, and open Fava at http://localhost:5000. Here’s what you should see.

Fava's Trial Balance view shows assets, income, and expenses in one place.

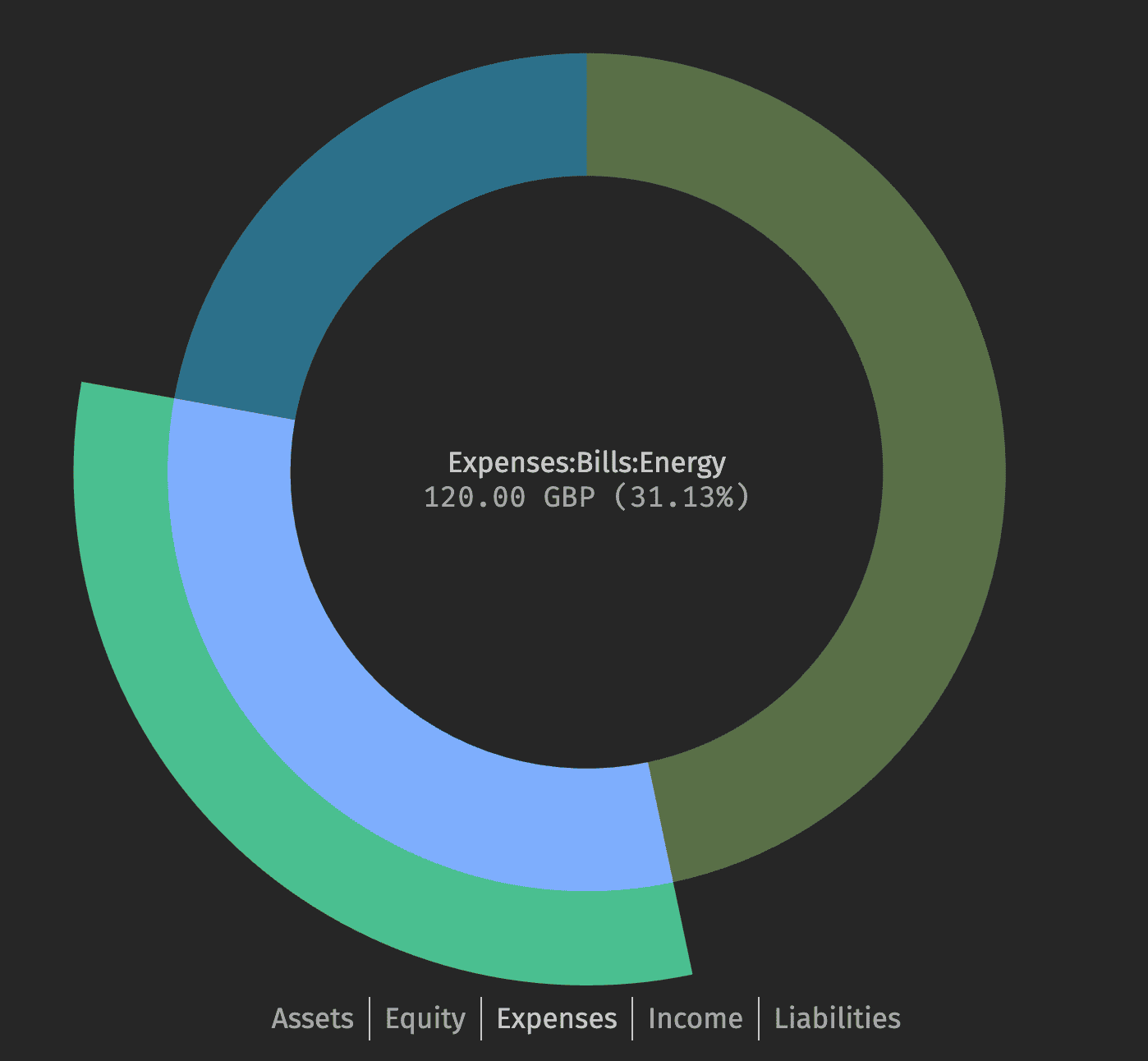

Sunburst charts make it easy to spot your biggest expense categories instantly.

Click around the different tabs. You’ll find that Fava gives you the following:

- Balance sheet: the state of your accounts at the current point in time. Basically think of it as an aggregate view of all your finances. You can answer questions like “what’s my net worth now?”, “how much money do I owe across my credit cards?” or “how much have I gained from investments?”

- Income statement: the sum of all the money flows into/out of your accounts. Think of it as a sum of all the income and expenses across time. You can answer questions like “how much did I earn from my job?”, “how much did I spend on Amazon?” or “did I spend more or less than last year?”

- Transaction history: a flat list of all transactions you have in your journal. A way to see and search any transaction you’ve made across any accounts in your system.

The Query Console lets you run SQL-like queries against your financial data.

There’s much more to Fava’s features (queries, multi-currency, plugins) as we’ll see later on in the post.

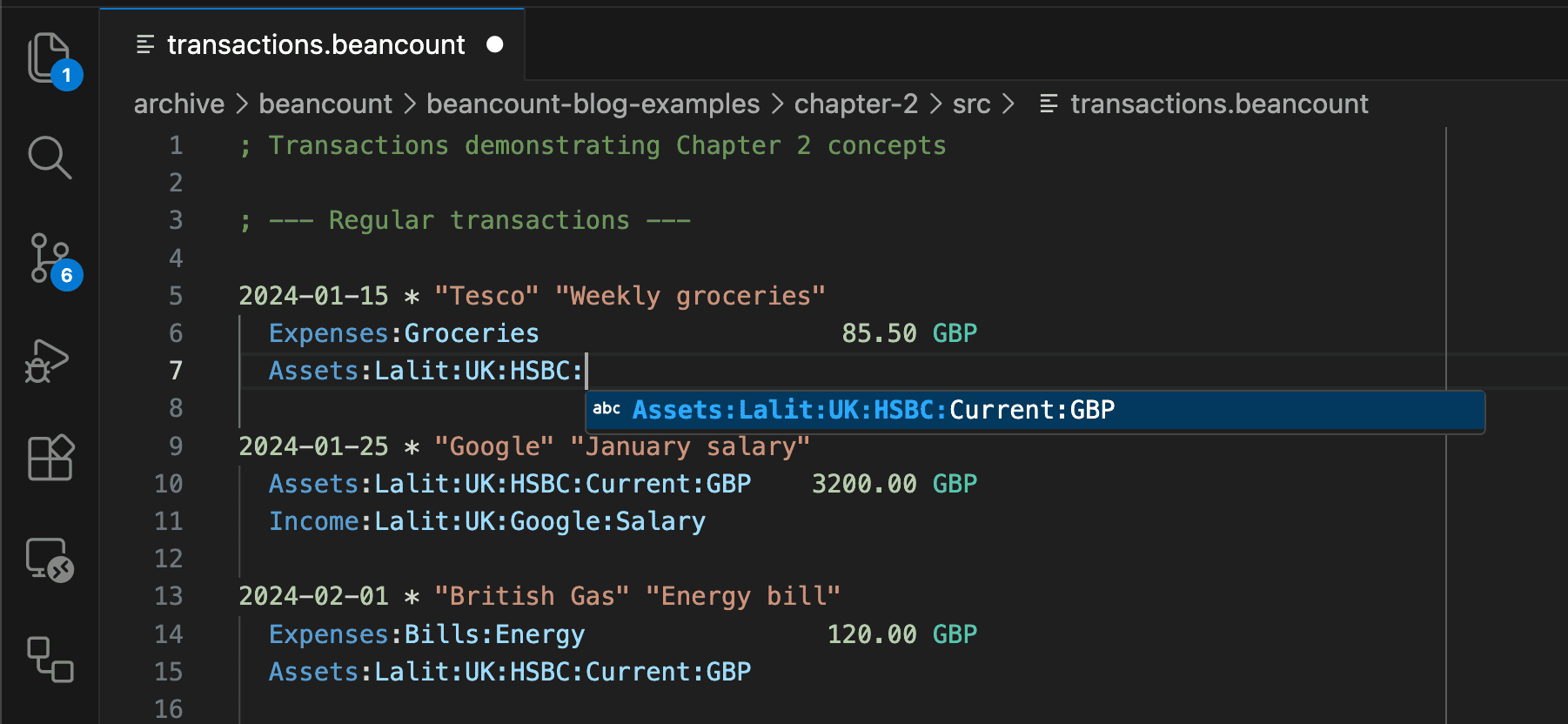

You can also explore the text journal itself using a text editor. For example, here’s a grocery run and a payslip in the Beancount transaction format:

; chapter-2/src/transactions.beancount

; Beancount auto-fills the second amount when it can be inferred.

2024-01-15 * "Tesco" "Weekly groceries"

Expenses:Groceries 85.50 GBP

Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP

2024-01-25 * "Google" "January salary"

Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP 3200.00 GBP

Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Salary

Go through the transactions and get a feel for the format. It might seem alien at first but trust me when I say soon it’ll feel like the most natural thing in the world!

With a VS Code extension, you get syntax highlighting and auto-completion for your accounts.

Now that you have a working system, I want to share the hard-won insights that aren’t in the official docs. This post isn’t going to be a full Beancount tutorial. The official docs are excellent for that (Fava even has a demo that you can try without downloading anything!).

Instead, I want to focus on the architecture: the decisions I wish I’d made correctly from day one. I’m writing this as if I’m speaking to my past self.

Start with one account

You don’t need to track everything on day one. Pick one account. Your main checking account is a good start. Get comfortable with the flow. Import statements, categorize transactions, check that balances match. Once that feels solid, add another account. Then another.

I started with my HSBC current account. Now, I have my whole financial life inside the system and I trust it wholeheartedly. But this happened one account at a time. If I tried to do everything in one go, I would certainly have been overwhelmed and given up on the whole thing.

Opening balances

Once you’ve picked your first account, you face an immediate problem: you may have opened that account years ago and there might already be thousands of transactions over that time. Trying to import them all in one go is another sure path to being overwhelmed and giving up.

Instead, a better idea is to pick a “starting date” at which you say “I will import everything from this day onwards”. But that poses its own problem: you already had money in that account, how do you tell Beancount it exists?

Well, Beancount has a pad directive that creates the balancing entry automatically:

; chapter-2/src/balance.beancount

2024-01-01 open Equity:Opening-Balances

2024-01-01 pad Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP Equity:Opening-Balances

2024-01-02 balance Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP 1500.00 GBP

The pad directive tells Beancount: “whatever amount is needed to make the balance assertion true, take it from Equity:Opening-Balances and put it in this account”. This is one of the rare cases you actually have to think about equity accounts (though not much beyond blindly using Equity:Opening-Balances!).

Structure That Scales

Adding a first account is easy and the second is straightforward, but adding a third, fourth, fifth… and you can easily find that things start becoming jumbled and messy. Just like code, putting a little bit of thought into the organization upfront goes a long way. This part covers the architectural decisions you’ll thank yourself later for.

Naming Asset and Liability accounts

The structure of asset and liability account names is very important, much more than I initially gave them credit for. It’s a good idea to keep as much information in them as possible. Here’s what I’ve settled on:

; chapter-2/src/accounts.beancount

2024-01-01 open Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP GBP

2024-01-01 open Assets:Lalit:UK:Barclays:Current:GBP GBP

2024-01-01 open Liabilities:Lalit:UK:AMEX:GBP GBP

The pattern is:

Type:Person:Region:Institution:Account:Currency

Why this structure? Because it’s a lot easier to remove detail than add it in later! I initially started by not having the country, the currency or my name in the account. But over time, I wanted to understand:

- How much money I have in the UK vs the US?

- How much cash (i.e. not investments) is in a certain currency?

- How much of our household wealth was in my wife’s accounts vs my own (discussed in more detail in Chapter 6)?

Having this information in the account name is great because Beancount’s SQL syntax makes it very easy to filter on account names. Want “all UK assets”? Filter on :UK:. Want “all HSBC accounts”? Filter on :HSBC:. Want “all GBP cash”? Filter on :GBP.

Powering up with Plugins

Once you have a structure, you want to ensure it stays clean. This is where Beancount’s Plugins come in.

Plugins are Python scripts that run when your ledger loads. They can validate data, modify entries, or even generate new transactions automatically. You load them in your journal file like this:

plugin "beancount.plugins.check_commodity"

Remember the transfer-in-flight pattern from Chapter 1? Here’s how it looks in Beancount:

; chapter-2/src/transactions.beancount

; Money leaves on Saturday

2024-03-16 * "Transfer to Barclays"

Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP -1000.00 GBP

Assets:Lalit:Transfers:Internal 1000.00 GBP

; Money arrives on Monday

2024-03-18 * "Transfer from HSBC"

Assets:Lalit:Transfers:Internal -1000.00 GBP

Assets:Lalit:UK:Barclays:Current:GBP 1000.00 GBP

Once both transactions are recorded, the transit account balance returns to zero, confirming the transfer is complete. If you record one leg of a transfer but forget the other, the transit account will simply show a non-zero balance.

Understanding where a non-zero balance in transfers is coming from is handled by my absolute favorite plugin, beancount_reds_plugins.zerosum. It’s responsible for matching both sides of a transaction and moving it to a separate account, meaning my Transfers:Internal account only contains the actual “pending” transactions. Making this account empty is a surprisingly satisfying little “minigame” during my weekly imports (though it never lasts for long!).

There are also a couple more plugins that make handling closed accounts better:

- beancount.plugins.close_tree - When you close an account, automatically closes all child accounts too. Useful as you move your banking between institutions.

- beancount_checkclosed.check_closed - Validates that closed accounts have zero balance and no transactions after the close date.

The boundary of your system

As you add accounts one by one, you’ll inevitably see money flowing to places you haven’t set up yet. Say you transfer £500 to a Natwest savings account you haven’t added to the system. Where does it go?

Specifically, use a named placeholder account in Equity:Transfers:

; chapter-2/src/transactions.beancount

2024-03-15 * "Transfer to savings (not yet tracked)"

Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP -500.00 GBP

Equity:Transfers:Natwest-Savings 500.00 GBP

This essentially says: “£500 went to Natwest Savings, which I’m not tracking yet”. Putting it in an equity account means it doesn’t pollute your balance sheet with incomplete information or your income statement with false expenses.

Note also the best practice of using a named equity account per untracked destination, not a generic bucket; this was a mistake I made when I did this initially. You’ll thank yourself when you import your Natwest savings account later, you can just do a search-replace to rename the accounts 6.

Organizing your repo

As you add these patterns (transit accounts, multiple institutions, liability accounts) your single journal.beancount file will start to become unwieldy. Just like good software architecture, you want to organize upfront to be easy to maintain as the system continues to grow.

This is what the structure looks like with the concepts we have right now (it’ll get more complicated as we go deeper!):

chapter-2/

├── journal.beancount # Main entry point, includes everything

├── src/

│ ├── accounts.beancount # Account definitions

│ ├── transactions.beancount # Primary transaction ledger

│ └── balance.beancount # Balance assertions

src/is what you write and edit (your “code”)journal.beancountis the entry point that includes everything- Later,

data/will hold inputs from the outside world (raw statements: PDFs, OFX, CSVs)

This organization is a small change but can make a big difference in your subconscious feeling about the state of your finances!

Exit ramp

At this point, you have a solid foundation for tracking multiple accounts. If you stop here, you have a robust, auditable system for manual bookkeeping. You could continue adding transactions by hand indefinitely, and you’d still be miles ahead of any spreadsheet in terms of correctness and visibility.

But manual entry is a chore, and as your financial life grows, it becomes a bottleneck. In the next chapter, we’ll see how to automate the tedious part: getting transactions from your bank statements into your ledger without losing the control that plain-text accounting gives you.

Chapter 3: Automated Import

Automation is king, but harder than it looks

Inputting transactions by hand works for some people, but I don’t have the patience for it. Ever since I was young, I’ve always wanted to automate everything: it’s the reason why I became a software engineer in the first place!

But full automation is a dead end. Most banks don’t offer APIs, and scraping breaks constantly. 2FA flows change 7, websites get redesigned, sessions expire. I tried this route, and it wasn’t worth it. Even in the US where aggregators like Plaid exist, coverage is patchy.8 In the UK, it’s impossible.

The hierarchy of data sources

So what actually works? Well ideally your financial institution gives you something you can write a script against. But what that might be is non-obvious and counter-intuitive. Here’s the hierarchy I’ve landed on over time:

- OFX is the gold standard. If your bank offers it, use it. The format is standardized, transactions have unique IDs, and deduplication is straightforward. Life is easy if you have good OFX.

- CSV is the deceptive runner-up. It seems like the logical choice. Structured data, right? But in practice, bank CSVs are often afterthoughts. I’ve seen column formats change without notice, “CSVs” that are actually weird custom formats spread over multiple lines, and rows coalesced in ways that lose critical information (like cost basis).

So what do you do when OFX isn’t available and CSV isn’t trustworthy? You turn to an unlikely hero.

Why PDFs beat CSVs

It sounds backwards, but PDFs are often the most reliable data source available.

Banks have a strong incentive to get PDFs right. Customers actually read them. They’re legal documents that get printed and filed. If a bank messes up a PDF statement, they hear about it immediately. If they break a CSV export, it might go months without anyone noticing.

The key insight is that bank statement PDFs are almost always columnar. Of course, this relies on the PDF having a proper text layer; if your bank sends you scanned images, you’re out of luck (though I’ve yet to encounter one that does). When you convert them to text while preserving the layout, you get something that looks like this:

Date Details Paid out Paid in Balance

15 Jan 24 TESCO STORES 1234 42.50 1,457.50

16 Jan 24 TFL TRAVEL 6.80 1,450.70

25 Jan 24 GOOGLE SALARY 3,200.00 4,650.70

The columns are aligned by spaces, which means you can parse them as fixed-width data. The approach works in three steps:

Convert PDF to text: Run

pdftotext -layout statement.pdf statement.txt. The-layoutflag preserves the original column alignment.Find the table boundaries: Bank statements have predictable markers. HSBC uses “BALANCE BROUGHT FORWARD” at the start and “BALANCE CARRIED FORWARD” at the end. You extract just the transaction rows between these markers.

Parse with fixed-width columns: Pandas’

read_fwffunction is designed exactly for this. You put this logic inside theextract()method of yourbeangulpimporter class, where it converts the text into a DataFrame:

# Inside your Importer class

df = pd.read_fwf(

io.StringIO(text),

colspecs=[(0, 10), (10, 40), (40, 52), (52, 64), (64, 80)],

names=['Date', 'Details', 'Paid out', 'Paid in', 'Balance']

)

The column positions come from inspecting the header row. In practice, I detect them dynamically by finding keywords like “Paid out” and “Paid in” in the header and using their character positions.

Once you have a DataFrame, generating Beancount transactions is straightforward. You write a small class that iterates through this DataFrame and maps each row to a Beancount Transaction object, filling in the date, amount, and payee. See my HSBC importer for a working example.

For 95% of my banks, this approach works great. However, there is one bank where the text spacing becomes very strange and so I need to use something else. That’s when I turn to Tabula, a Java CLI that extracts data tables from PDFs, even very complex ones.

The main reason I don’t use it all the time is that it’s much slower. But it also succeeds in the cases where pdftotext fails. I run it to get a structured JSON output, from which I create transactions (see my HSBC US credit card importer).

I’m sure some readers will have worries about the fragility of what I’ve described here. I can tell you from experience that in three years, neither my UK nor my US HSBC PDF importer has ever broken. Neither has my Schwab one, and my Aviva one has only needed a single change. So I can personally vouch that this approach works and works well.

From raw data to transactions

OK, so now you have statements. What do you do then? There are two pieces to the puzzle: parsing statements into transactions, and categorizing those transactions.

For parsing, Beancount has an official importer framework called beangulp. You write a Python class that knows how to read a particular file format (the skeleton importer in chapter-3/ already uses this API). Beangulp handles the mechanics: identifying which importer handles which file, extracting transactions, and deduplicating against existing entries.

But beangulp just extracts transactions without making any judgment on which account the transaction should be booked against. It doesn’t know that Tesco is groceries or that British Airways is an airline. I go to a new restaurant. How does the system know that is a restaurant?

This leads to a very important conclusion: we cannot fully automate importing transactions for bank accounts and credit cards. However, that doesn’t mean we have to enter things manually either. There’s a middle ground.

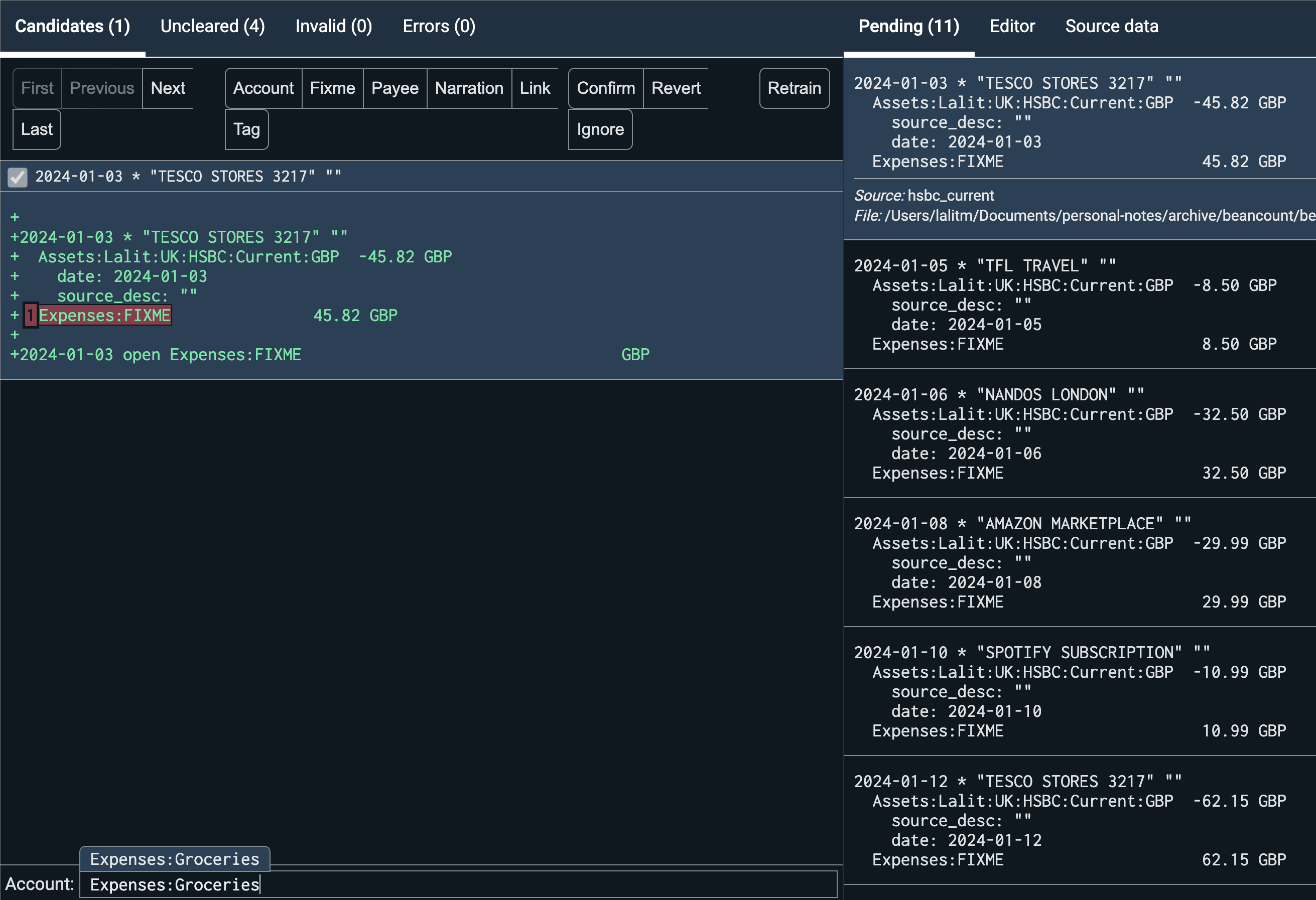

Enter beancount-import9 (Note: this is a standalone tool, distinct from Fava’s built-in import features). It’s a web UI that uses your beangulp importers and adds a categorization layer on top. You run it, it opens in your browser, and it presents pending transactions one by one for review. Think of it as a staging area where you approve or tweak before anything hits your ledger.

For each transaction, it shows the raw data from your statement alongside a suggested categorization. You can accept the suggestion, override it with a different account, or skip it entirely. Once you decide, it moves to the next one. The interface is simple, mostly keyboard-driven and optimized for speed.

The import UI allows you to manually categorize transactions, like this Tesco grocery run, while the system learns your preferences.

The categorization uses machine learning (old-school decision trees, running locally, no LLMs, no cloud). It learns from your previous choices: the first time you see “Tesco”, you pick “Expenses:Groceries”, and the second time it auto-suggests and you just hit Enter. After a few weeks, the system should know 90% of the types of transactions you make and it’s easy to correct the ones which it doesn’t.

Once you’re proficient, a month’s worth of transactions takes 5-10 minutes. Most are repeats and you’re just hitting Enter. You only pause on genuinely new merchants. This is the core of my weekly ritual, and why I’ve found categorization has not become a chore, even after doing it for years.

Exit ramp

With automated imports and semi-automated categorization, the “hard work” of bookkeeping is mostly solved. For many, this is the endgame: a perfect record of where every penny went, updated in minutes each week.

But your net worth isn’t just cash in a bank account. It’s also the stocks, bonds, and funds that grow (or shrink) over time. Tracking these requires a few more tools to handle cost basis, dividends, and market prices. We’ll tackle those in Chapter 4.

Chapter 4: Investments

Now for investments. It’s where things get more interesting, and I think there’s less material out there covering the nitty-gritty. Here are some lessons I’ve learned over the years.

The Unified Mental Model

The most important thing to realize is that Beancount treats everything as a commodity.

A share of Apple (AAPL) is a commodity. A US Dollar (USD) is a commodity. A British Pound (GBP) is a commodity. While Beancount can infer these on the fly, you’ll typically declare them explicitly in your journal (e.g., 2024-01-01 commodity AAPL).10

This explicit declaration is a small but critical architectural win: it prevents a simple typo from creating a phantom currency, and it provides the metadata that advanced reporting plugins (like those used to calculate your portfolio performance) rely on to work correctly.

This means you don’t “buy stocks with money”. You simply exchange one commodity for another. The syntax for buying shares is identical to the syntax for exchanging currency.

The Account Structure

Just like with bank accounts, I break investments down by institution and security.

; chapter-4/src/accounts.beancount

2024-01-01 open Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:USD USD

2024-01-01 open Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL AAPL

2024-01-01 open Assets:Lalit:UK:Vanguard:ISA:GBP GBP

2024-01-01 open Assets:Lalit:UK:Vanguard:ISA:VWRL VWRL

Cash in a brokerage is just another holding named by currency (GBP, USD), while stock holdings use their ticker (AAPL, VWRL).

But you also need to track the flows generated by these assets: capital gains, dividends, commissions, and withholding taxes. I create specific accounts for each security:

2024-01-01 open Income:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL:Dividends USD

2024-01-01 open Income:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL:Capital-Gains USD

Why so granular? It’s the same reason I name assets fully: aggregation up the tree is trivial; disaggregation after the fact is impossible. If you track all your dividends in a single Income:Dividends account, it’s easy to know “how much dividends did I earn total?”. But if you want to know “what was my AAPL dividend yield this year?”, you’re out of luck. Track at the leaf (Income:IB:AAPL:Dividends), and you can answer both questions.

The Notation

With our accounts defined, we can now record the actual movement of assets. We use {} to denote cost (what we paid per unit) and @ to denote price (what the unit is worth now).

Example 1: Buying Stock Exchanging 1850 USD for 10 shares of Apple.

2024-01-10 * "BUY AAPL"

Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL 10 AAPL {185.00 USD} @ 185.00 USD

Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:USD -1850.00 USD

The {185.00 USD} is the cost basis and the @ 185.00 USD is the price. Beancount uses the cost basis to track lots and calculate capital gains.

Note: Cost basis rules depend heavily on where you are. In the US, you track cost basis of individual lots. In the UK, we have special “Section 104” pooling rules.11 I discuss this more in Chapter 5.

Example 2: Buying Currency Exchanging 950 GBP for 98,000 INR.

2024-03-02 * "Wise" "GBP to INR"

Assets:Lalit:UK:Wise:INR 98000.00 INR @@ 950.00 GBP

Assets:Lalit:UK:Wise:GBP -950.00 GBP

In the second example, @@ specifies the total cost rather than the per-unit cost.

Example 3: Selling Stock Selling 5 shares of Apple at $190 (bought at $185).

2024-01-30 * "SELL AAPL"

Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL -5 AAPL {185.00 USD} @ 190.00 USD

Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:USD 950.00 USD

Income:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL:Capital-Gains -25.00 USD

Here we specify the lot we’re selling ({185.00 USD}) and the price we’re selling it at (@ 190.00 USD). The difference is the capital gain (or loss).

But the principle is identical: Assets:Wise:INR and Assets:Brokerage:AAPL are just accounts holding commodities.

Automation

Investments are very different from normal accounts in that they can be fully automated. No categorization needed: a buy is a buy, a dividend is a dividend. You don’t have new merchants to worry about.

This means you can skip beancount-import’s web UI and run your beangulp importers directly with output going straight to the ledger. To help inspire you, I’ve open-sourced my personal collection of importers (IB, Vanguard, Schwab, and more) in the beancount-lalitm repo.

Handling Account Sprawl

However, one annoyance is that creating those granular accounts for every single stock (...:AAPL:Dividends, ...:AAPL:Commissions, etc.) is tedious. To solve this, I wrote the ancillary_accounts plugin. Instead of manual account creation, you just add metadata to the main holding account:

2023-02-01 open Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:BAC BAC

ancillary_commission_currency: "USD"

ancillary_distribution_currency: "USD"

ancillary_withholding_tax_currency: "USD"

ancillary_capital_gains_currency: "USD"

The plugin automatically generates the corresponding income and expense accounts for you.

Corporate Actions

I also use a plugin called stock_split to handle corporate actions. It retroactively adjusts historical transactions when a stock splits, keeping quantities and prices consistent with post-split values so your charts don’t show a sudden, fake drop in value.

The Value of Things (Prices)

We have the quantities (10 AAPL, 98,000 INR), but to calculate a single “Net Worth” number, we need to know what they are worth in your home currency. This requires prices for both:

; chapter-4/src/prices.beancount

2024-01-10 price AAPL 185.50 USD ; Stock price in USD

2024-01-10 price USD 0.79 GBP ; Currency price in GBP

I automate this using a daily CI job. A script fetches the latest stock prices and forex rates from AlphaVantage and commits them to prices.beancount. You can find the script here.

In practice, I actually have three price files:

prices.beancount- auto-fetched daily for as many securities as possible.prices-manual.beancount- for securities without automatic feeds (like some pension funds). I input these manually once a month.prices-delisted.beancount- historical prices for securities no longer trading. This saves me from making API calls which would fail anyway.

The Payoff

With this data, Fava comes alive. To see the full potential of these reports, I’ve included a demo/ folder in the companion repo with 2+ years of history. Run ./scripts/quickstart.sh demo and you’ll see the payoff.

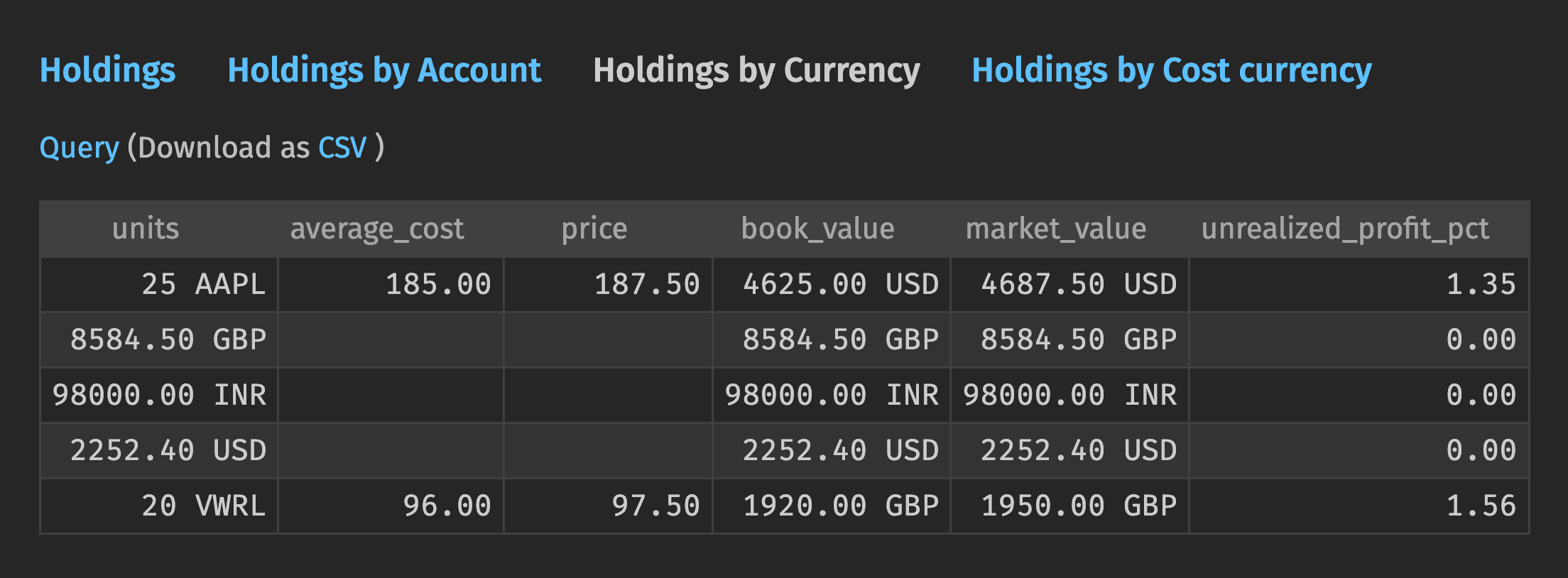

The Holdings page now shows your positions with their cost basis and current market value.

The Holdings report automatically calculates the market value of your assets using live price data.

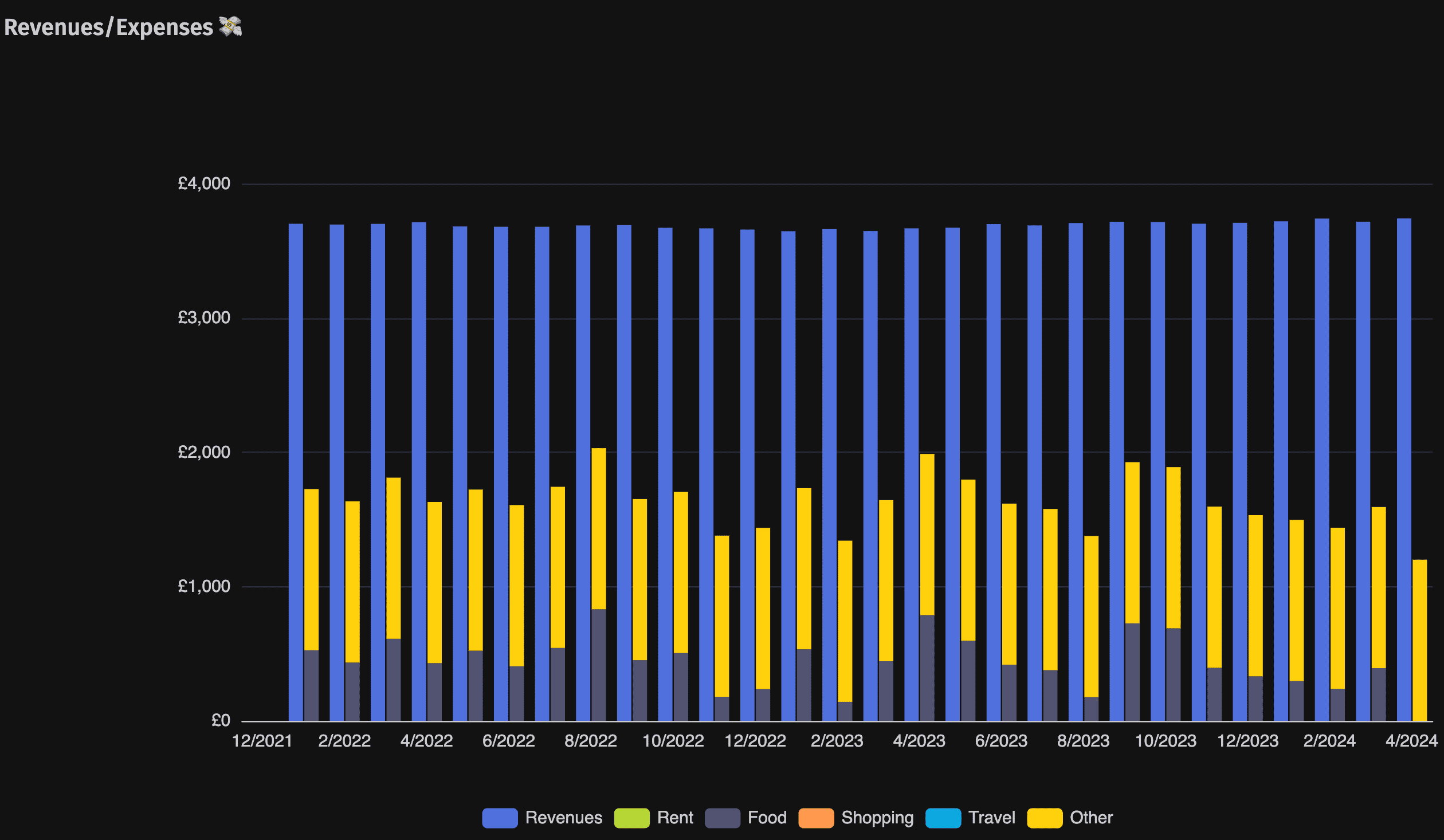

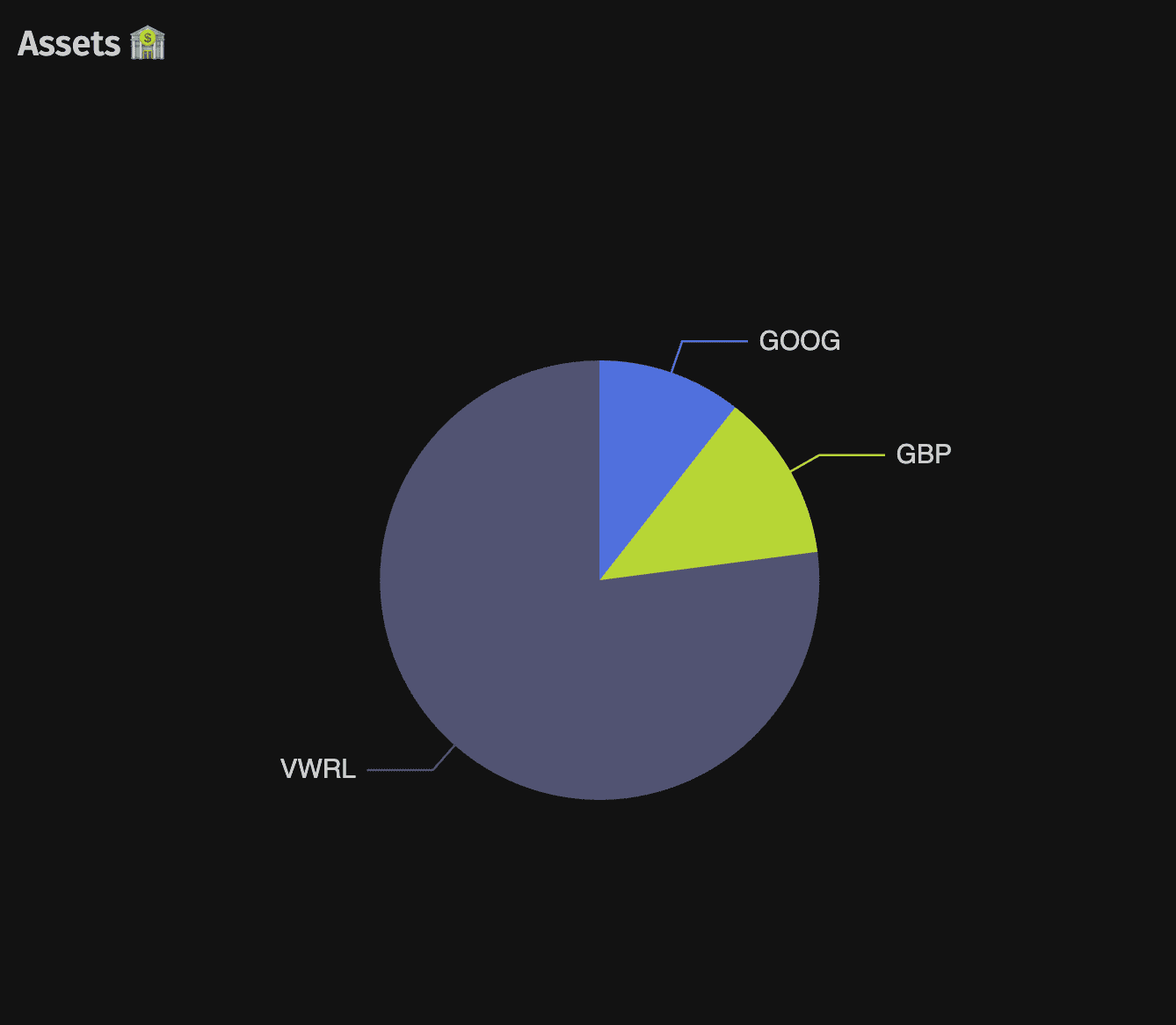

In the demo environment, you can also see how plugins like fava-dashboards build custom visualizations. The plugin uses beanquery (Beancount’s SQL-like query language) to fetch data and renders interactive charts. It’s the best way to track long-term trends and asset allocation at a glance.

Custom dashboards (shown here using the demo data) allow you to track long-term trends and asset allocation at a glance.

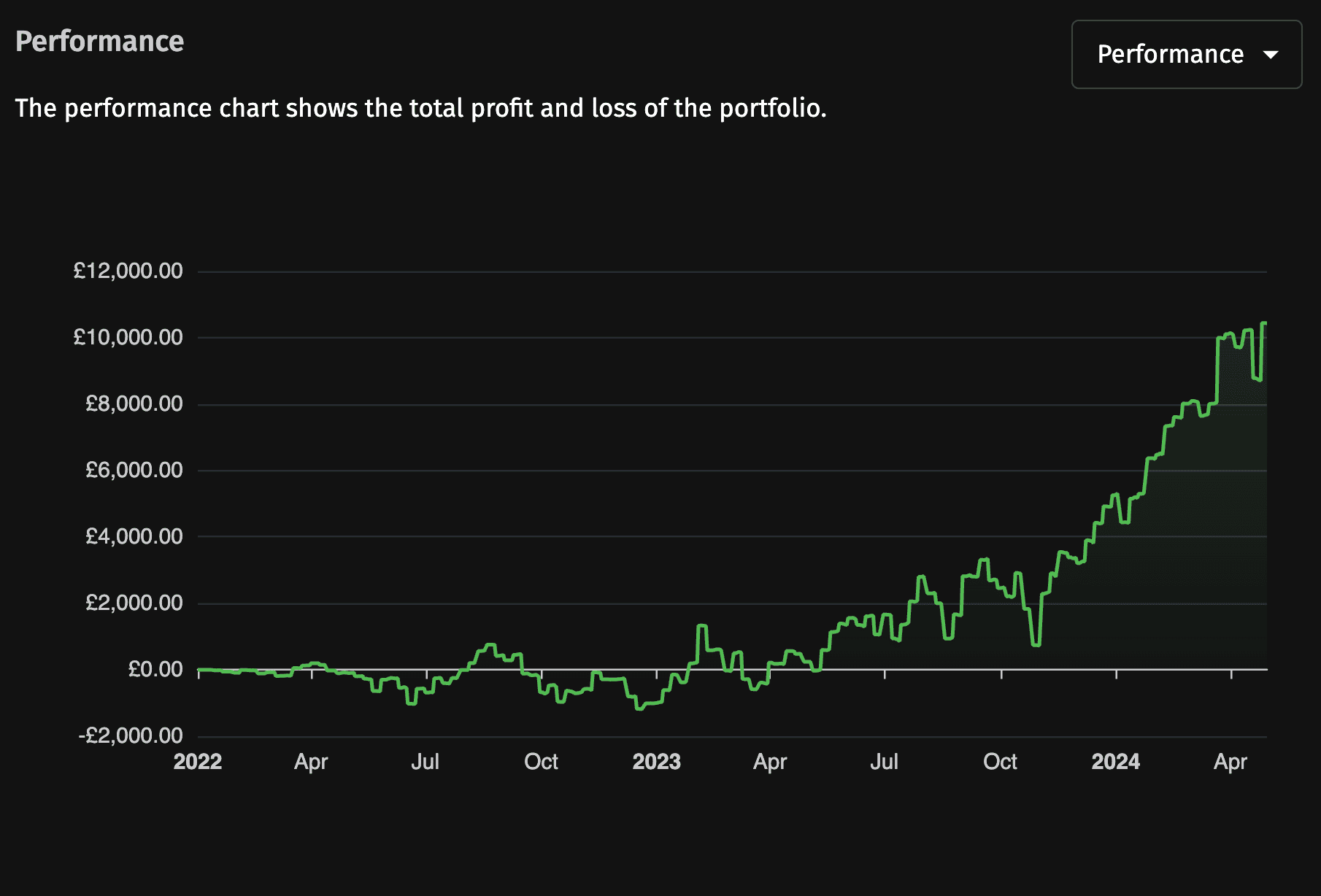

And with fava-portfolio-returns, you can calculate your true Time-Weighted Return (TWR) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) to see if you’re actually beating the market. It accounts for cash flows properly, so adding money mid-year doesn’t inflate your returns.

The portfolio returns plugin (using the demo data) calculates your actual investment performance, net of cash flows.

Exit ramp

You now have a system that tracks your entire financial world: from the coffee you bought this morning to the capital gains in your brokerage account. For most people, this is a complete solution.

However, as you collect more data, you’ll find you want to look at it in different ways. Maybe you want a simplified view for daily use and a detailed one for tax season. Or maybe you’re not the only person in your household. In the final chapters, we’ll see how to scale this system to handle multiple views and multiple people.

Chapter 5: Multiple Views

Day-to-day, I want a simple view of my finances. Take-home pay as a single number, investments without tax calculations cluttering the screen. But at tax time, I need detail. Every payslip line item and capital gains calculated the way HMRC wants them. Recording the same transaction twice would be maintenance hell. So instead, I extract multiple views from a single journal.

I think of these as “lenses” on the data. Some lenses aggregate: rolling up transactions into balances, summaries, or dashboards. Others transform: collapsing detail you don’t need day-to-day, or expanding it when you do. Both read from the same source files; nothing is duplicated.

Aggregated views

Fava is great for interactive exploration, but I also want textual snapshots I can version control. I have a script that generates daily summaries showing account balances, and a CI workflow that commits them automatically. In my setup this runs on a self-hosted Gitea instance on hardware I control, so the raw ledger never leaves machines I own. If you prefer, you can keep everything local-only or push to an encrypted remote; GitHub Actions works the same way if you’re comfortable with that trade-off. This gives me:

- A record of how balances changed day to day

- An immutable snapshot at tax time of what the system showed

- Git as audit trail: “What was my net worth on March 15th 2023?” is answerable with

git checkout

The key script is archive.py. It uses the beanquery library to write SQL scripts over your journal and generate textual reports:

# Generate balance sheet in GBP

sql = '''

SELECT account,

round(sum(number(convert(value(position, '2024-12-31'), 'GBP', '2024-12-31'))), 2) as value

FROM OPEN ON 2024-01-01 CLOSE ON 2024-12-31 CLEAR

GROUP BY account

HAVING round(sum(number), 2) != 0

ORDER BY account;

'''

I run this for each calendar year and tax year, generating files like:

networth.txt- Single-line net worth in each currencybalance-sheet.txt- Net worth breakdown by accountholdings.txt- Investment positions with cost basis and market value

Here’s what networth.txt looks like:

gbp usd

------------- -------------

15978.42 GBP 19973.02 USD

This is the concrete “one number I trust”: a single net-worth snapshot in my reporting currency, generated from the full ledger and price data.

And holdings.txt:

account units curr avg_cost price book_val mkt_val

--------------------------------- ----- ---- -------- ----- -------- -------

Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP 4914.50 GBP 1.00 1.00 4914.50 4914.50

Assets:Lalit:UK:Vanguard:ISA:VWRL 20.00 VWRL 96.00 97.50 1920.00 1950.00

Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL 5.00 AAPL 146.15 150.40 730.75 752.00

My Gitea workflow is very simple too:

on:

schedule:

- cron: '00 7 * * *' # Run daily at 7am

jobs:

update:

steps:

- run: uv run scripts/archive.py outputs/ journal.beancount 2024-01-01 2024-12-31

- run: git commit -am "Regen reports" && git push

Transformed views

Sometimes I want to change how transactions work fundamentally. This is a more advanced technique: while Aggregated views read data, Transformed views temporarily rewrite it in memory to simplify reality.

I have three transformed views, each for a different purpose:

- Net - my daily driver. Collapses payslip details into a single take-home number.

- Gross - breaks down payslip line items for tax time analysis.

- CGT - a view that includes a “virtual currency” tracking capital gains the way my tax authority calculates them.

The linchpin is the rename_accounts plugin. It lets me keep one copy of all transactions and rename accounts on the fly to show or hide detail.

Gross vs net payslip

Let me start with the simpler example. In gross view, my payslip shows every line item:

2024-01-25 * "Google" "January salary"

Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP 3500.00 GBP ; Take-home pay

Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Salary -5000.00 GBP ; Gross salary

Expenses:Lalit:UK:Google:Income-Tax 1000.00 GBP ; Tax withheld

Expenses:Lalit:UK:Google:National-Insurance 400.00 GBP ; NI contribution

Expenses:Lalit:UK:Google:Pension 100.00 GBP ; Pension contribution

Useful for analyzing my tax situation. But day-to-day, I don’t care about the breakdown. In net view, the same transaction collapses:

; chapter-5/journal-net.beancount

include "journal.beancount"

plugin "beancount_reds_plugins.rename_accounts.rename_accounts" "{

'Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Salary': 'Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Net-Income',

'Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Bonus': 'Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Net-Income',

'Expenses:Lalit:UK:Google:Income-Tax': 'Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Net-Income',

'Expenses:Lalit:UK:Google:National-Insurance': 'Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Net-Income',

'Expenses:Lalit:UK:Google:Pension': 'Income:Lalit:UK:Google:Net-Income',

}"

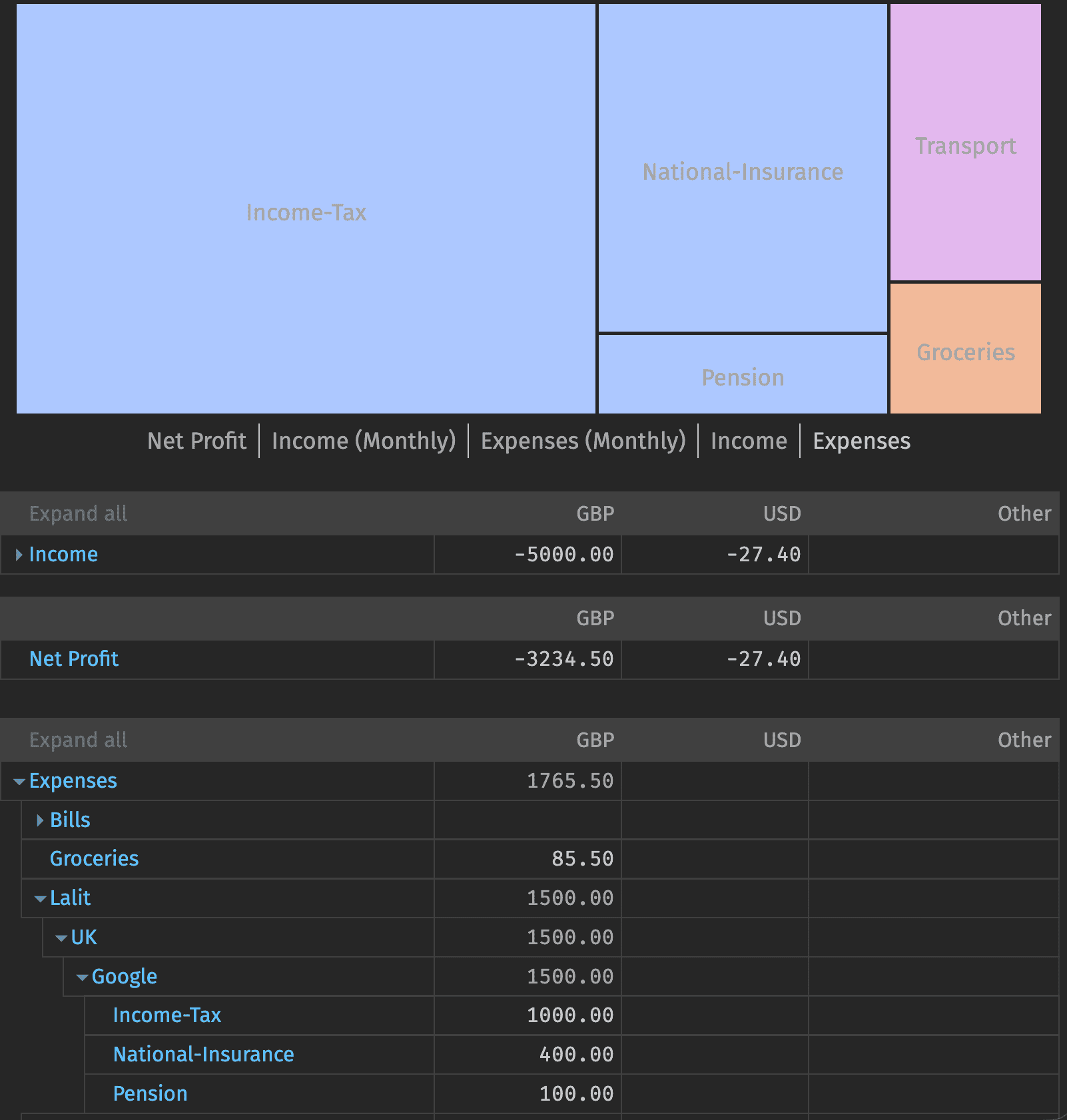

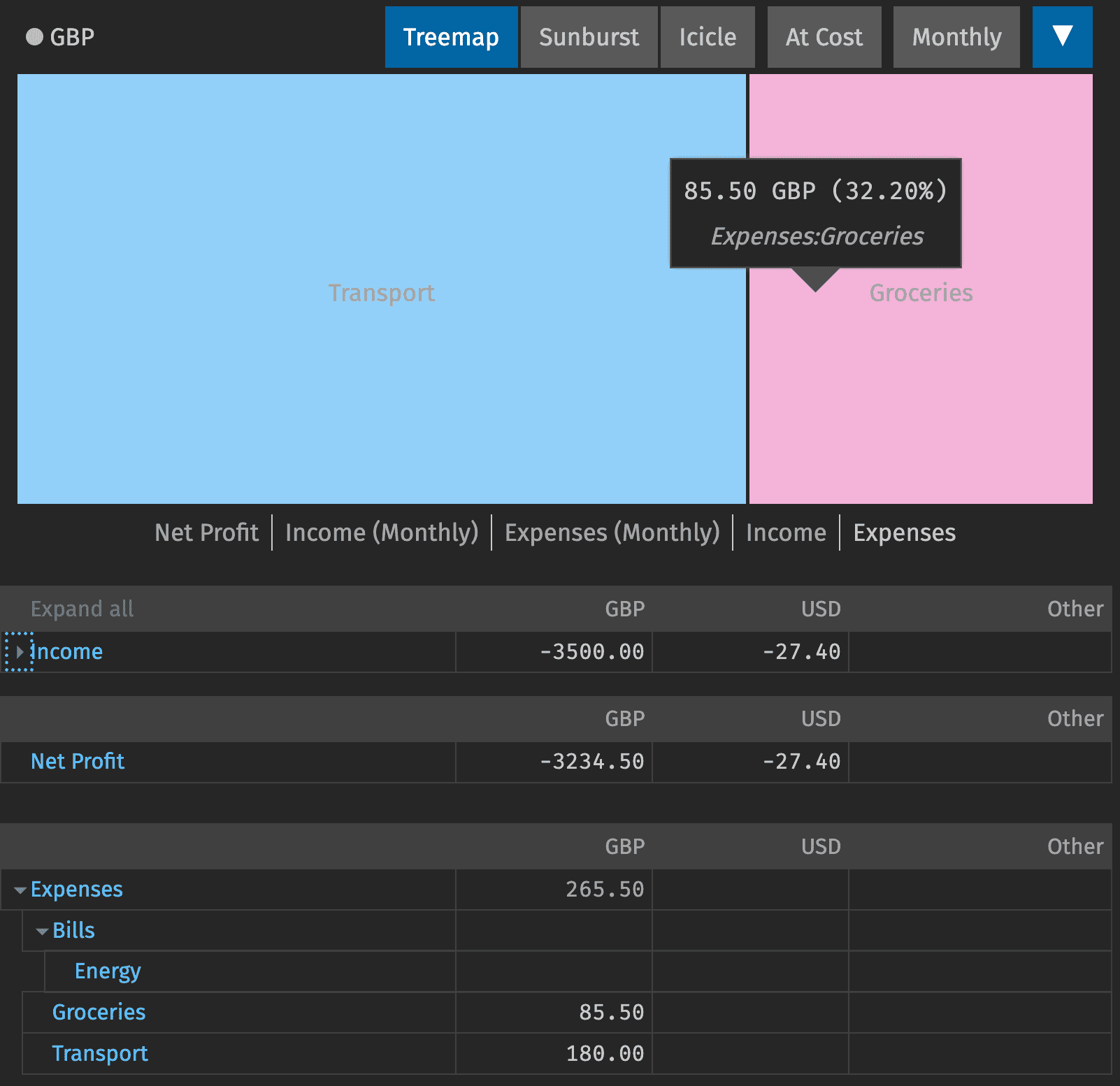

Because Income is stored as a negative number and Expenses as positive numbers, merging them into one account mathematically subtracts the tax from the gross pay, leaving just the net amount. The difference should be obvious if I compare the Income Statements on Fava:

The Gross view is essential for tax season, but the detailed line items for taxes and insurance often dwarf your actual spending data.

The Net view collapses those details into a single take-home number, making your everyday expenses much easier to analyze.

Tracking capital gains for tax

We can use this same renaming technique to handle a much more complex beast: Capital Gains Tax.

Your broker reports one gain number, but your tax authority may calculate another. In the UK, where I live, we have specific rules like “Section 104 pooling” (averaging cost basis) and “bed-and-breakfasting” (wash sale rules).

To handle this, I use a virtual currency called CGT-GBP that represents “pounds of gain HMRC cares about”. My plugin, uk_cgt_lots, calculates this number and automatically appends a self-balancing pair of Equity postings to the original sale transaction:

2024-06-15 * "SELL AAPL"

Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL -10 AAPL {150.00 USD} @ 175.00 USD

Assets:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:USD 1750.00 USD

Income:Lalit:US:IB:Brokerage:AAPL:Capital-Gains -250.00 USD

; The following postings are generated by the uk_cgt_lots plugin:

Equity:Taxable-Capital-Gains 195.00 CGT-GBP

Equity:Taxable-Capital-Gains-Placeholder -195.00 CGT-GBP

Since both legs are in Equity, they remain invisible on my Income Statement in my daily “Net” view. In fact, I use rename_accounts to collapse them into a single account so they net to zero:

; journal-net.beancount

plugin "beancount_reds_plugins.rename_accounts.rename_accounts" "{

'Equity:Taxable-Capital-Gains-Placeholder' : 'Equity:Taxable-Capital-Gains',

}"

But when I want to see my tax liability, I switch to the CGT View. This view renames the “Placeholder” to a visible Revenue account:

; journal-cgt.beancount

plugin "beancount_reds_plugins.rename_accounts.rename_accounts" "{

'Equity:Taxable-Capital-Gains-Placeholder' : 'Revenues:Taxable-Capital-Gains',

}"

Now, the -195.00 becomes Revenue, which shows up as profit on my tax report. The matching +195.00 remains in Equity. This allows me to have “Schrödinger’s Capital Gains”: they exist for the taxman, but not for my daily budget, all controlled by which view I load.

I don’t calculate the tax owed since that’s too complicated with allowances, rates, and bands; the system just tracks the gains. At tax time, I sum up the CGT-GBP balance and do the actual calculation on the tax form.

Exit ramp

By separating your “source of truth” from your “lenses,” you get a system that grows with you. You can add new plugins or virtual currencies to solve specific problems (like taxes) without ever touching the raw transactions you’ve already imported.

In the final chapter, we’ll see the ultimate application of this: combining two people’s financial lives into one unified view.

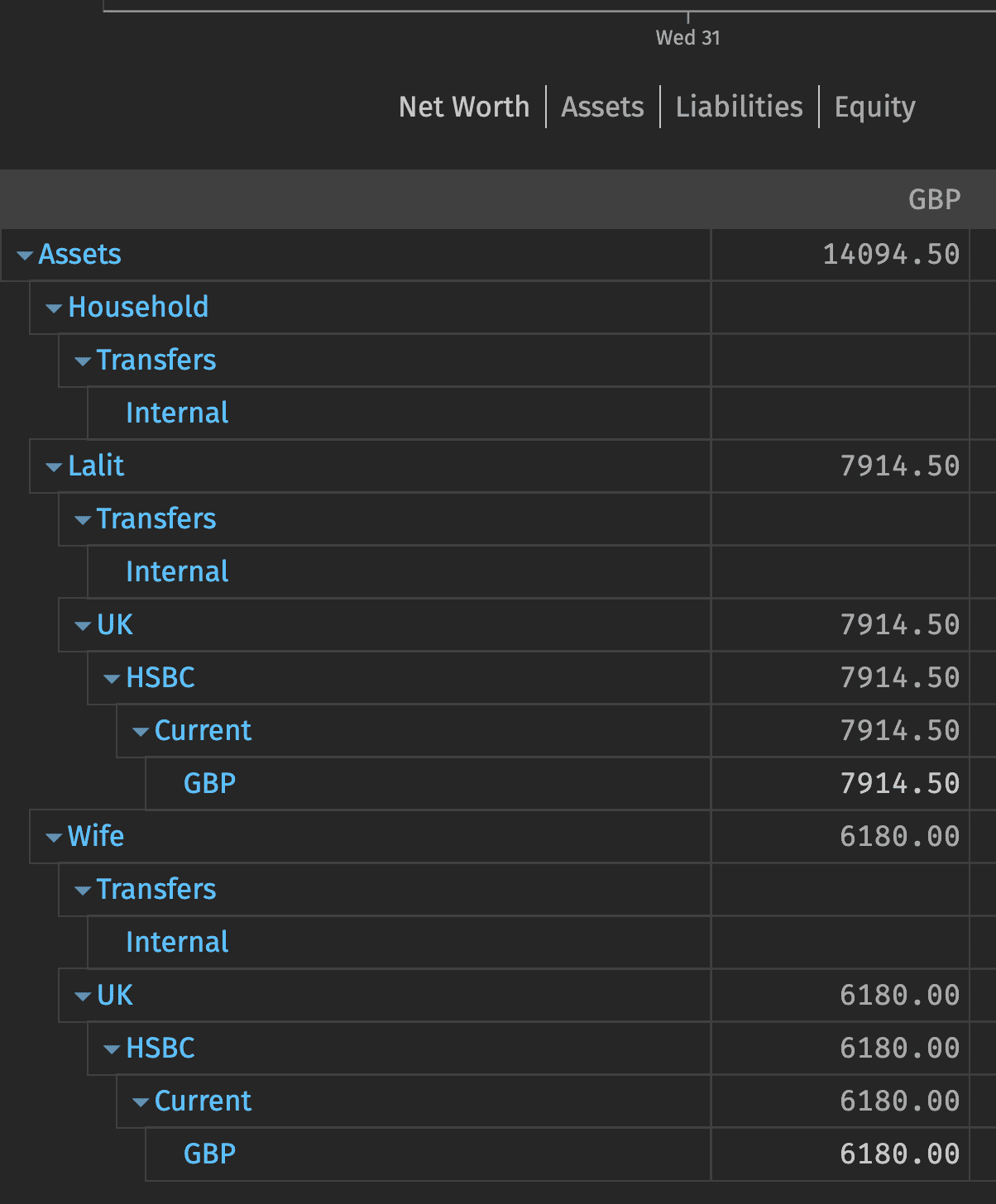

Chapter 6: Two People, One Number

I got married at the start of the year, which brought a fundamental change to how I manage my finances. While many couples use joint accounts, we prefer to keep our individual accounts and perform occasional “normalization” transfers. However, we view our combined resources as shared household wealth.

This created a reporting paradox that I had to solve in Beancount.

The Paradox

When I transfer £500 to my wife for my share of the bills, two things are true simultaneously:

- The Individual Truth: From my perspective, £500 is “gone” (an expense). From her perspective, £500 has “arrived” (income).

- The Household Truth: For the household, the net worth hasn’t changed. Money just moved from the left pocket to the right pocket.

In a traditional system, you usually have to pick one truth. In Beancount, we can have both.

The Composable Architecture

To solve this, I treat the household as a composable system of three distinct entities: Me, Her, and Shared Definitions. We use Beancount’s include feature to build the specific “lens” we need at any given moment:

- Lalit’s View = Shared Definitions + Lalit’s Transactions

- Wife’s View = Shared Definitions + Wife’s Transactions

- Household View = Shared Definitions + Lalit’s Transactions + Wife’s Transactions + Translation Logic

For example, the household view literally just includes the other files (alongside the translation logic we’ll see in a moment):

; chapter-6/total/journal-net.beancount

include "../common/src/commodities.beancount"

include "../common/src/accounts.beancount"

include "../lalit/src/journal.beancount"

include "../wife/src/journal.beancount"

; ... Translation Logic follows

Implementation: The Directory Structure

This architecture is reflected directly in the repository structure:

chapter-6/

├── common/ # Shared configuration

│ └── src/

│ ├── accounts.beancount # Shared expense accounts (e.g. Expenses:Groceries)

│ └── commodities.beancount

├── lalit/ # My stuff

│ ├── src/ # My ledger

│ └── data/ # My statement PDFs/CSVs

├── wife/ # Wife's stuff

│ ├── src/ # Her ledger

│ └── data/ # Her statement PDFs/CSVs

└── total/ # Combined household view

└── journal-net.beancount # Entry point with Translation Logic

The Rules of Engagement

For this to work without constant manual adjustment, we follow two simple rules:

Rule 1: Assets and Liabilities are Private.

Bank accounts always include the person’s name in the path (e.g., Assets:Lalit:HSBC or Assets:Wife:HSBC). We never use a generic Assets:Checking account. Legal ownership of the cash always matters.

Rule 2: Expenses are Public. Shared expenses like groceries or electricity use a generic name without a person prefix.

; chapter-6/common/src/accounts.beancount

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Groceries GBP

When I buy groceries, I record it in my ledger using the shared account. We don’t track “who owes what” for individual grocery runs; we just track that the household spent the money. We accept that we lose the ability to split shared expenses by person, but the gain in simplicity is worth it.

The “Magic”: Solving the Transfer Paradox

Finally, we use the rename_accounts plugin in the total/ folder to resolve the transfer paradox.

In my ledger, a transfer looks like a simple expense:

; chapter-6/lalit/src/transactions.beancount

2024-01-20 * "Transfer to Wife"

Expenses:Lalit:Transfers:Wife 500.00 GBP

Assets:Lalit:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP

In her ledger, it looks like income:

; chapter-6/wife/src/transactions.beancount

2024-01-20 * "Transfer from Lalit"

Assets:Wife:UK:HSBC:Current:GBP 500.00 GBP

Income:Wife:Transfers:Lalit

The “Translation Logic” in the combined view renames these into a shared transit account:

; chapter-6/total/journal-net.beancount

plugin "beancount_reds_plugins.rename_accounts.rename_accounts" "{

'Expenses:Lalit:Transfers:Wife': 'Assets:Household:Transfers:Internal',

'Income:Wife:Transfers:Lalit': 'Assets:Household:Transfers:Internal',

}"

Now, when Fava loads the combined view, it sees £500 leave my account and enter Assets:Household:Transfers:Internal, and then £500 leave that same account and enter her bank account. The transit account nets to zero, and our household net worth remains unchanged.

The Result

This setup gives us the best of both worlds. I can maintain my own financial autonomy and see my personal “runway,” while we can simultaneously monitor our combined progress toward shared goals.

The final result: a unified household view that tracks legal ownership without sacrificing the "One Number" net worth total.

That’s the full system (see chapter-6 for the complete multi-person structure). But how do I actually use it week to week?

The weekly ritual

Now here’s how I keep it current: the “20 minutes a week” I mentioned at the start:

Getting statements: During the week, banks email me saying a statement is available. Some attach PDFs directly; others require a login. Either way, I snooze the emails (I use inbox zero) until the weekend. For my wife’s accounts, I nudge her once a month and she drops stuff in a shared Drive folder.

Running imports: On the weekend, I work through my snoozed emails. Note that I’m not updating every single account every week. I only download statements for the 3-4 accounts that saw activity; long-term investments often just get a monthly or quarterly check-in. I move each file to the correct

data/subfolder for that institution (e.g.,data/hsbc-uk-current/). My importer pipeline automatically runspdftotextto extract text so the parsers can read it.Categorizing: I launch beancount-import, which opens a web UI in my browser:

python -m beancount_import.webserver --journal lalit/journal-net.beancountAs I mentioned before, most transactions auto-categorize and I’m just hitting Enter: I buy groceries from the same place, pay my hosting costs to the same provider etc. New merchants do need some manual work, but it’s a matter of typing a few characters and again pressing Enter.

Formatting and checking: I run

bean-format(a Beancount utility that normalizes indentation and aligns amounts) to keep my transactions file tidy. This makes git diffs cleaner. Then I open Fava for a quick sanity check:fava lalit/journal-net.beancountAre transfer accounts zeroed out? Do expenses look legit? How are investments doing? If it all checks out, commit and push.

That’s it. I try to stick to doing this every week, but sometimes I’m on holiday or just have other commitments. In that case, it’s 40 minutes every two weeks. The system is forgiving; I’m never behind for too long.

I also have some automation helping me out: during the week, I have a CI workflow that runs daily, regenerates summaries, and commits them. Whenever I want, I can check the repo and see what the numbers look like. I particularly like this because I can easily see the before/after numbers in a single file, so I can spot check “does this make sense”. And of course at any time, I can also open Fava if I want to go a bit deeper.

Conclusion

That 2021 tax disaster feels like a lifetime ago. What started as “there must be a better way” became a system I actually trust. One number, always current, completely under my control.

The specifics will evolve as life changes and tools improve, but three principles have held for years now. I expect them to hold for decades:

Double-entry everywhere. Every transaction balances. Money never appears from nowhere or vanishes into nothing. When something doesn’t add up, you know immediately.

Plain text as the source of truth. Your financial history lives in files you can read, diff, grep, and version control. No vendor lock-in, no opaque databases, no trusting a third party with your data.

Track at the leaf. Record transactions at the most granular level that makes sense. You can always aggregate up (Income:Dividends from Income:IB:AAPL:Dividends), but you can never disaggregate down. Capture the detail; collapse it later with views.

Finance systems are deeply personal. This post isn’t meant to say this is the system everyone should use, just what’s worked for me over several years.

Each chapter here could be its own post, so if you want me to go deeper on imports, investments, or the multi-person setup, let me know!